In New Zealand, approximately 160 people develop cervical cancer each year, and about 50 die from it.

Cervical Cancer

HPV Primary Screening is recommended for those in Aotearoa New Zealand who have a cervix and are aged between the ages of 25 – 69.

People should be encouraged to participate in the NCSP if they are a wāhine/woman or person with a cervix, aged 25 to 69, who:

- has ever had intimate skin-to-skin or any sexual activity (even if they haven’t been sexually active for decades)

- has only had non-penetrative sex (i.e., oral sex)

- is straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or queer

- is transgender, gender diverse, or non-binary and has a cervix

- has only been with one sexual partner

- has had the HPV vaccination or not

- is pregnant or has had a baby

- has been through menopause.

Visit Time to Screen or phone 0800 729 729 if you’re looking for information about cervical screening.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is caused by some strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is a group of very common viruses that infect about four out of five people at some time in their lives, passed on by sexual contact. HPV causes cells to grow abnormally, and over time, these abnormalities can lead to cancer.

PLEASE NOTE: Just because you may have had HPV immunisation this does not mean that you are protected from developing cervical cancer.

Cervical Cancer – Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of cervical cancer can include:

- bleeding or spotting between periods

- bleeding or spotting after sex

- bleeding or spotting after periods have stopped (after menopause)

- unusual and persistent discharge from your vagina

- persistent pain in your pelvis

- pain during sex.

See your GP or a gynaecologist if you notice any changes or experience any persistent symptoms that worry you. Any changes should ALWAYS be investigated.

Cervical Cancer – Risk Factors

The most important risk factor for cervical cancer is persistent HPV infection. Other factors may contribute, including:

- HPV: Infection with the human papillomavirus is the most important risk factor for cervical cancer.

- not having regular screening: this increases the risk of developing cervical cancer as early changes to cells go undetected.

- smoking: tobacco is a factor in causing many types of cancer, including cervical cancer. Those who smoke are twice as likely as non-smokers to develop cervical cancer

- genetics: some people are more likely to get cancer than others (family history)

Cervical Cancer – Diagnosis

The majority of people diagnosed with cervical cancer are identified through a cervical smear test.

Cervical Smear

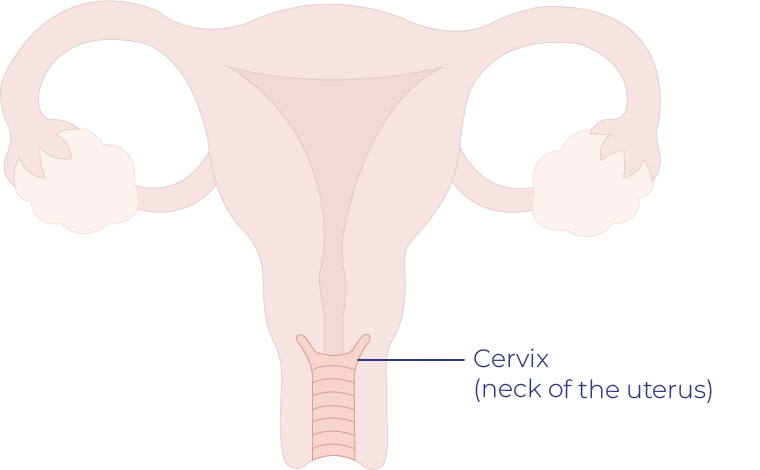

During a smear your GP, nurse or gynaecologist scrapes and brushes cells from your cervix, these are then sent away to be tested for abnormalities.

A smear test can detect abnormalities in the cervix, including cancer cells

Colposcopy

A colposcopy is a procedure to closely examine your cervix for signs of disease. During a colposcopy, an instrument called a colposcope is used by your doctor to carry out this procedure.

Your doctor may recommend having a colposcopy if your cervical smear test results confirm any abnormalities. If your doctor finds an unusual area of cells during a colposcopy, a sample of tissue can be collected for laboratory testing.

Screening for HPV

HPV primary screening looks for the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV). For most people an HPV infection clears by itself within two years (especially in people under 30). Sometimes HPV can cause a persistent infection, so screening helps us know if additional diagnostic testing or treatment is required.

- A HPV vaginal swab test, either by self-test or assisted by a clinician

- A liquid based cytology sample, which is tested for HPV

If HPV is detected cytology will be processed automatically without the person needing to return for another test.

The most common investigations for cervical cancer are:

MRI Scan

This is the most effective way of seeing how far the main part of the cancer has spread through the cervix and how close it is to the bladder and the bowel.

CT Scan

This scan is very good for looking at lymph nodes in the pelvis and the chest which is where the cancer is most likely to spread to first.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan

You will be given a small amount of low dose radioactive glucose, which is ‘picked up’ by rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells. The position of the radioactive glucose can be seen on the scan.

If you are diagnosed with cervical cancer, you will undergo more tests to work out the type and stage of your cancer. There are two main types of cervical cancer:

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

This is the most common type of cervical cancer. It starts in the ‘skin-like’ cells that cover the outer surface of the cervix at the top of the vagina.

Adenocarcinoma

This is a less common type of cervical cancer. It starts in the glandular cells in the cervical canal.

Don’t feel silly going to the doctor – it’s your body, you know it better than anyone else!

Cervical Cancer – Treatment

Treatment is dependent on how far the cervical cancer has progressed this is known as ‘the stage’. But other factors can also affect your treatment options, including the exact location of the cancer within the cervix, the type of cancer (squamous cell or adenocarcinoma), your age and overall health, and whether you want to have children.

Treatments for cervical cancer include surgery, radiation treatment, chemotherapy or a combination of these treatments.

Surgery

Surgery is common for small cancers found only within the cervix. The extent of the cancer in the cervix will determine the type of surgery needed.

Cone Biopsy

Some very early cervical cancers may be treated with cone biopsy. During a cone biopsy, tissue is removed from the cervix while you are anaesthetised and sent to the laboratory to be studied. Cutting away the tissue also removes the abnormal cells. The tissue that grows back is likely to be normal, in which case no more treatment is needed. A cone biopsy takes less than an hour.

Trachelectomy

The removal of the cervix.

Total Hysterectomy

The removal of the uterus and cervix.

Radical Hysterectomy

The removal of the uterus and about two centimetres of upper vagina and tissues around the cervix.

When you have either type of hysterectomy, you will also have a:

Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

- The removal of lymph nodes within the pelvis.

Bilateral salpingo oophorectomy

- The removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes.

Cervical Cancer – Stages

All cancers are given a ‘stage’. The stage indicates the size of the tumour and the extent of its spread throughout the body. Cervical cancers may be given the following stages:

Stage 0

Abnormal cells are found in the first layer of cells lining the cervix.

Stage I

The cancer is found only in the cervix.

Stage II

The cancer has spread beyond the cervix to the upper portion of the vagina.

Stage III

The cancer has spread throughout the pelvic area. It may involve the lower portion of the vagina, ureters and surrounding lymph nodes.

Stage IV

The cancer has spread to nearby organs such as the bladder or rectum, or to other parts of the body (eg: lungs, liver, bones).

I believe I have these symptoms – what next?

Please make an appointment to see your GP

Write a list of the symptoms that are present and any other concerns to take with you to your GP or gynaecologist

You should tell them about any changes to your body that you have noticed and if you or anybody in your family has had cancer or been tested for genetic faults.

It’s extremely important to note that if you feel your symptoms are not the ordinary for you, are persistent and have gotten worse that you advocate for your health.

1. Take a list of the symptoms that are present- give your GP as much information as you can.

2. Consider your whānau/family history and discuss this with your doctor. Call whānau/family and try to get a gauge on what cancers if any have been present. Please note that a gynaecological cancer can be present even if there has been no whānau/family history of one.

3. Ask your GP for a second opinion or referral to a specialist

4. You are by rights allowed to take someone along with you to your GP and specialist visits for moral support, it’s great to have someone there especially when being given a lot of new information.

5. NEVER feel silly or like you are overreacting by seeking the advice of a medical professional YOU know your body better than anyone else.