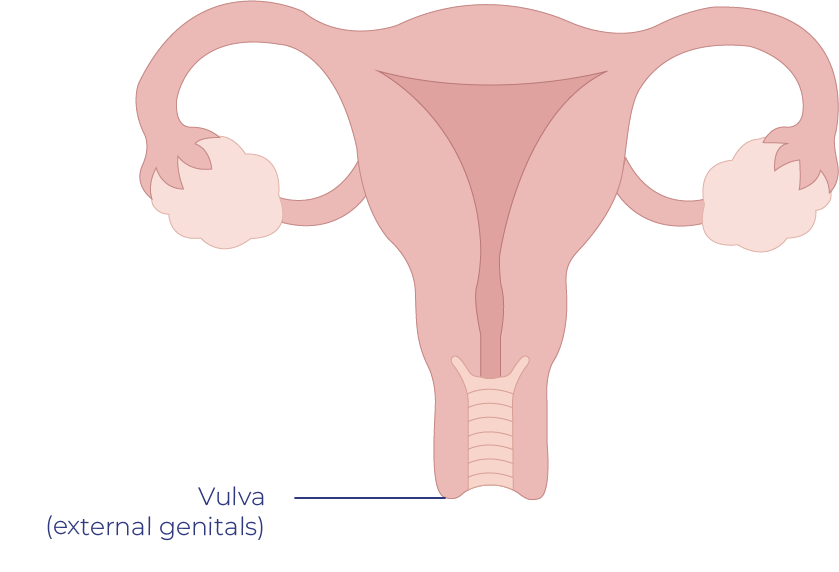

Cancer of the vulva (also known as vulvar cancer) is a rare type of cancer and occurs on the outer surface area of the genitalia. The vulva includes the opening of the vagina (sometimes called the vestibule), the labia majora (outer lips), the labia minora (inner lips), the clitoris and the Bartholin’s glands (two small glands on either side of the vagina The Bartholin glands are found just inside the opening of the vagina — one on each side. These glands produce a mucus-like fluid that acts as a lubricant during sex.

Vulval Cancer

See your GP or a gynaecologist if you notice any changes or experience any persistent symptoms that worry you. Any changes should ALWAYS be investigated.

Vulval Cancer – Risk Factors

There is no definitive way to know for sure if you will get vulval cancer. Some people get it without being at high risk. However there are several factors that may increase the possibility that you will develop vulval cancer, including:

- Ageing

- Certain types of the HPV human papilloma virus. HPV is a sexually transmitted infection that increases the risk of several cancers, including vulval cancer and cervical cancer. Many young, sexually active people are exposed to HPV, but for most the infection goes away on its own. For some, the infection causes cell changes and increases the risk of cancer in the future.

- skin conditions affecting the vulva, such as lichen sclerosis

- Smoking

- Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), where the cells in the vulva are abnormal and at risk of turning cancerous. Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a skin disease where abnormal cells develop in the surface layers of the skin covering the vulva. It is not vulval cancer but could turn into a cancer. This may take many years. Some doctors call it pre cancer although many people with VIN will not develop cancer.

- Having a weakened immune system. People who take medications to suppress the immune system, such as those who’ve undergone organ transplant, and those with conditions that weaken the immune system, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have an increased risk of vulvar cancer.

- Having a history of precancerous conditions of the vulva. Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia is a precancerous condition that increases the risk of vulval cancer. Most cases of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia will never develop into cancer, but a small number do go on to become invasive vulval cancer. For this reason, your doctor may recommend treatment to remove the area of abnormal cells and periodic follow-up checks.

Don’t feel silly going to the doctor – it’s your body, you know it better than anyone else!

Vulval Cancer – Treatment

Treatment often involves surgery to remove the cancer and a small amount of the healthy tissue surrounding it.

If the vulval cancer is in the advanced stages, surgery may require removing the entire vulva. The earlier vulval cancer is diagnosed, the less likely such an extensive surgery is required.

It’s so important to know the signs and get an early diagnosis! Never delay in taking charge of your health – look after yourself!

Vulval Cancer – Stages

Vulval cancer is given one of four Stages, these are:

Stage I

A small tumour that is confined to the vulva or the area of skin between your vaginal opening and anus (perineum). This is when the cancer hasn’t spread itself to the lymph nodes or other areas of the body.

Stage II

Tumours are those that have grown to include the lower portions of the urethra, vagina and or anus.

Stage III

The cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage IV

The cancer has spread itself more extensively throughout the lymph nodes, or that it has spread to the upper portions of the urethra or vagina, the bladder, pelvic bone or rectum, or the cancer has spread itself (metastasised) to other parts of your body.

I believe I have these symptoms – what next?

Please make an appointment to see your GP

Write a list of the symptoms that are present and any other concerns to take with you to your GP or gynaecologist

You should tell them about any changes to your body that you have noticed. You should tell them if you or anybody in your family has had cancer or been tested for genetic faults.

It’s extremely important to note that if you feel your symptoms are not the ordinary for you, are persistent and have gotten worse that you advocate for your health.

1. Take a list of the symptoms that are present- give your GP as much information as you can.

2. Consider your whānau/family history and discuss this with your doctor. Call whānau/family and try to get a gauge on what cancers if any have been present. Please note that a gynaecological cancer can be present even if there has been no whānau/family history of one.

3. Ask your GP for a second opinion or referral to a specialist

4. You are by rights allowed to take someone along with you to your GP and specialist visits for moral support, it’s great to have someone there especially when being given a lot of new information.

5. NEVER feel silly or like you are overreacting by seeking the advice of a medical professional YOU know your body better than anyone else.